Note: This is the second post in a series about AI focused on understanding the current moment (Q1 2026). The pace at which AI is evolving means this will quickly become archival / out of date 🙃

The right mindset: “Trust No One”

The first and most essential rule of truly evaluating and understanding modern AI systems is that you cannot trust the claims of someone that sells AI solutions. This rules out most of the major model providers, big tech, and other people that make the most noise in the space. In many cases, AI isn’t even close to an appropriate solution for a problem, but that isn’t going to stop someone from trying to sell you on it.

(For the record, it also rules out trusting me as an author, but we’ll work around that together.)

The second rule of evaluating an AI system is that you cannot fully trust any recent claims. People are allowed to say anything they want in marketing materials, but it needs to be proven in the market over time. Nothing that has been built in the recent AI boom has had enough time to truly land or be studied longitudinally. There hasn’t been enough time and we need to remind ourselves of that often.

So what is AI anyway?

Keeping those rules in mind, let’s look for some common ground and definitions far away from the current marketing cycle. You’ve likely heard the term “Artificial Intelligence” before in your life, and you’ve definitely heard it before ChatGPT existed, but do any of us really have a firm grasp of what it means now?

Looking to the past can be helpful for perspective, and we’ll be exploring a physical oddity called a “book” in our search for it. The book is called “The Handbook of Artificial Intelligence” by Barr and Feigenbaum. It was assembled by academics and industry experts in the mid-1970s, was published in 1981 (which predates your humble author and hopefully helps alleviate our mutual trust problem), and aims to make the history and terminology of AI accessible to a 1980s audience.

This is how they defined Artificial Intelligence on Page 1 (after a lovely dedication to their graduate students):

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) is the part of computer science concerned with designing intelligent computer systems, that is, systems that exhibit the characteristics we associate with intelligence in human behavior - understanding language, learning, reasoning, solving problems, and so on

…

These experimental systems include programs that

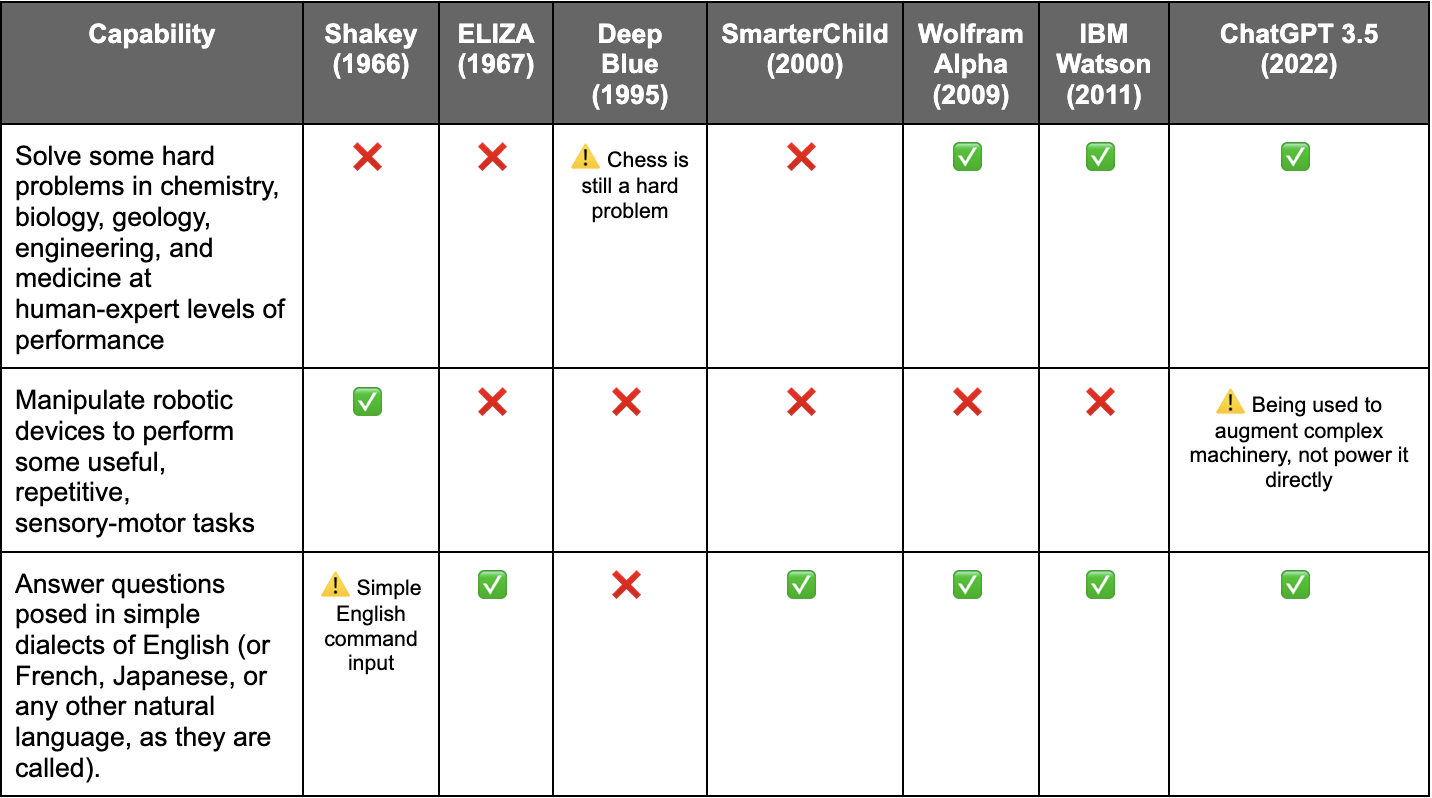

solve some hard problems in chemistry, biology, geology, engineering, and medicine at human-expert levels of performance,manipulate robotic devices to perform some useful, repetitive, sensory-motor tasks, andanswer questions posed in simple dialects of English (or French, Japanese, or any other natural language, as they are called).

There is every indication that useful AI programs will play an important part in the evolving role of computers in our lives - a role that has changed, in our lifetimes, from remote to commonplace and that, if current expectations about computing cost and power are correct, is likely to evolve further from useful to essential.

This is prescient considering that nearly 45 years have passed since publication. Much of the early chapters of the book spend time navigating their own recency biases, delving into the scientific, mechanical, and mathematical breakthroughs of the 1930s and 40s that advanced practical applications and theory of AI as a field.

This is still a weighty definition with a lot to unpack, especially if you’re not already invested in computer science. But it provides several quantifiable markers that we can test against AI products across time. To illustrate this, we’ll use a few different examples that have tried to optimize for at least one of these criteria that both pre-date and post-date the definition:

Seeing it like this, it’s obvious why the current moment might feel different to some. AI technology has, recently and for the first time, become generalized and accessible, able to perform multiple high-difficulty tasks from within a single, unified product package.

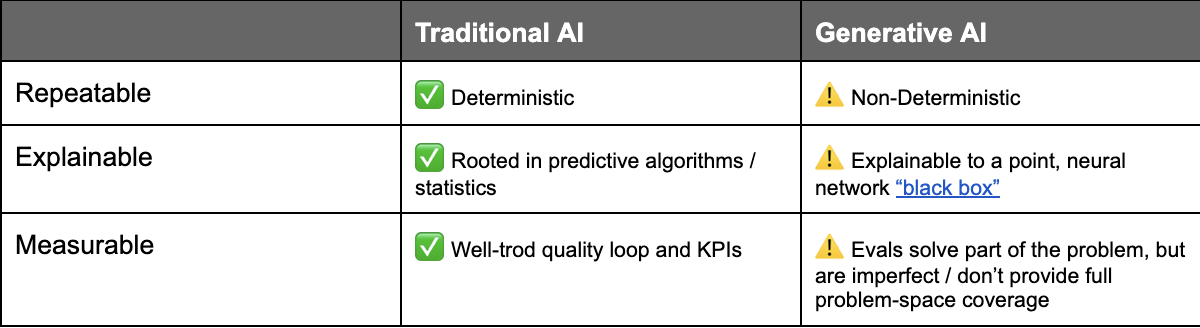

What changed over the last century to get us to this moment? Why now? We’re still figuring that out, but within the field of AI technology there seems to be an emerging consensus that a line has been crossed between “Traditional AI/ML (Machine Learning)” and “Generative AI”.

Traditional AI/ML is largely rooted in predictive math and statistics and has defined modern production applications within the tech industry. I am not an expert, but have eaten lunch with a few of them and have gleaned that these systems are largely defined by the amount of human involvement / time investment to achieve usable quality. And a lot of yelling about “overfit”.

They can be supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised in nature and often involve humans training, deploying, and monitoring them over time. Being rooted in math and having a large body of published research means that these systems are considered to be well-understood / low-risk. If you put in the same variables, the equation should yield the same response every time. As a business or a consumer, you have a lot to trust beyond the engineer deploying the tech.

Generative AI is a different beast entirely, and uses artificial neural networks, pre-existing training data, and a loosely predictive nature to generate content. It is arguably more complex and has had less time to be fully understood within academia or published research, but has incredible potential and capability that will not wait for that bar to be passed before deployment.

This is the core trade-off to consider between the two: do you want something predictable, but less potentially capable? Or something broadly capable, but inherently unpredictable? And when we say “inherently unpredictable”, we mean exactly that. GenAI systems are non-deterministic in nature and are not guaranteed to give the same output when given identical input variables / conditions.

This might not sound like a big deal, but it is. However you’re consuming AI downstream, this should shape how you view and fundamentally trust the tech itself:

Ok, but why should I give a damn about AI?

So why should you care about AI solving math problems or flailing mechanical arms about or yelling non-sequitors in French? For one, because beyond the imitation of intelligence is the promise of actual intelligence (we are likely not there yet). For another, there is undeniable capability being demonstrated by GenAI technology now that didn’t exist before, even if it does have caveats.

It might not be consistent and it might not always be right, but neither are people. An AI agent only needs to perform better than the lowest quality bar set by a human to upheave an existing business, career or livelihood. It’s worth considering whether or not that applies to ourselves and our own expertise.

It’s an interesting enough question that we decided to answer it for ourselves at Pelidum. Our expertise is online safety, so we wanted to start with that and evaluate whether or not current AI systems can compete with the production processes and systems we’ve spent our careers building.

Up next, we’ll talk about moving beyond the “chatbot” use case of AI, before moving onto local deployment in a time of no VRAM, and then sharing data and results from a year of online safety testing.

If you’re working along similar lines and would like to collaborate, please feel free to reach out to info@pelidum.com or contact Peter, Liam, or myself directly on LinkedIn. If you’d like to complain about a minor detail in this post, please contact Peter directly.

Mike Castner

CTO, Pelidum

Interested in learning more?

Book some time with us for more information on what we do and how we can help your organisation